A drash for Parsha Shemot

But first, a song "Kotsk"

[Refren]

[Refrain]

Kayn kotsk furt men nit,

To Kotsk we do not ride,

Kayn kotsk gayt men.

To Kotsk we walk.

Vayl kotsk iz dokh bimkoym hamikdesh (2)

Because Kotsk is a sacred place (2)

Kayn kotsk miz men oyle-reygl zayn,

To Kotsk we must go on foot,

oyle-reygl zayn.

go on foot.

1. Reygl iz dokh der taytsh a fis,

1. "Regl" means "a foot",

Kayn kotsk miz men gayn tsi fis.

To Kotsk we go on foot,

Zingendik, tantsndik!

Singing, dancing!

In az khsidim gayen kayn kotsk,

And when Hasidim go to Kotsk,

Gayt men mit a tants! (2)

They dance as they walk! (2)

[Refren]

[Refrain]

2. Reygl iz dokh der taytsh a geveyntshaft,

"Regl" means a "custom",

Men darf zikh gevaynen tsi gayn kayn kotsk,

You have to become accustomed to walking to Kotsk,

Zingendik, tantsndik!

Singing, dancing!

In az khsidim gayen kayn kotsk,

And when Hasidim go to Kotsk,

Gayt men mit a tants! (2)

They dance as they walk. (2)

[Refren]

[Refrain]

3. Reygl iz dokh der taytsh a yontev,

3."Regl" means a holy day,

Git yontev, git-yontev, git-yontev!

A happy holiday, a happy holiday!

Zingendik, tantsndik!

Singing, dancing!

In az khsidim gayen kayn kotsk,

And when Hasidim go to Kotsk,

Geyt men mit a tants! (2)

They dance as they walk. (2)

(Kotsk sung by Henry Sapoznik with the band Youngers of Zion)

Today’s parsha, Shemot, is almost too rich. In it we have the origin story of the superhero Moses, but it reads like a dream; a fantastic tangle of interconnected themes. To name just a few: birth, death, water, blood, G-d, names, and feet. As a dance guy, I’m going to focus on, obviously, feet, but also on the many names that eponymously give this parsha its name: shemot.

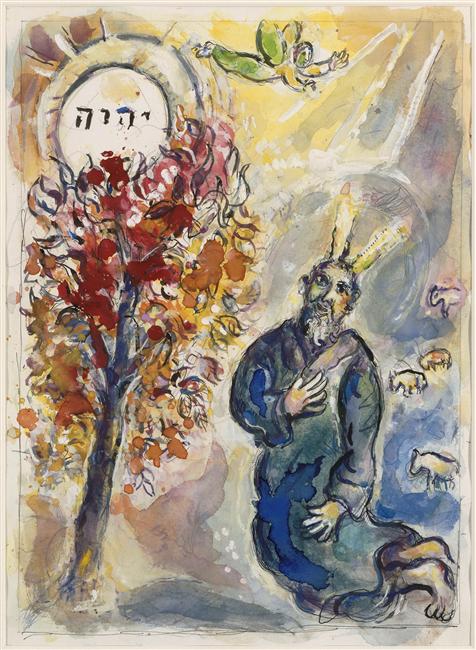

The song I began this drash with, Kotsk, is about a Chassidic journey to the court of Kostsk. And this parsha concerns both a physical journey, from Egypt to Midian and back to Egypt, and also Moses’ spiritual journey, from being kind of Jewish and kind of Egyptian, to being a Jew like no other. And while Moses reconnects with his Jewishness on this journey, we discover G-d reconnecting with the Jewish people, all through being observant and sensitive. G-d hears the people and their suffering, and Moses sees, and wonders over, the burning bush. How long and how closely must one watch a burning bush to notice it is not being devoured by the flame? When Moses approaches the bush, we get the first reference to feet; G-d tells Moses to cast the sandals from his feet, as this is holy ground. This is the exquisite turning point in the journey, the still moment at the end of the pendulum’s swing. This moment is most resonant to me as a dancer and dance leader.

Just like Moses, we mostly use our feet to go places. It’s a prosaic thing, walking, running, traveling, journeying. Yet dance is not practical, we’re not trying to get anywhere. I often find myself chastising young dancers who disrupt a dance by going too fast in relation to others that “this is not a race”. No, when we dance, we’re not necessarily trying to get to some destination, in general we’re simply going around in circles. “Going around in circles” is often used to announce a pointless pursuit, but Judaism has a different view of circles.

Biblical Hebrew has a number of words to describe dance. One of the major ones is Machol, the root of which, chul, could describe turning or gyrating. In context it often refers to the dance of women- it is the word used to describe Miram and the women’s dance at the Red Sea, and has a connotation of a call and response dance-one of the simplest choreographic ideas. It is often a synonym for joy, and is frequently paired with the word for drum- tof – as in both the Miriam episode and the 150th psalm- Halleluhu betof u’machol.

Rikud has become another Modern Hebrew word for dance, but in the Torah it mostly refers to athletic capering and leaping like lambs and rams, or mountains when the Red Sea parted. Psalm 114: “Heharim rakdu k’eylim”- the mountains skipped like rams. It is also one of the words used to describe King David’s leaping, spinning dance before the Ark.

Hagag refers to processions, and gives us the word Chag for a pilgrimage festival, and more generally any holiday.

And finally, Sivuv refers to circling, or encircling. It’s the word used to describe how Joshua encircled Jericho, how worshippers encircled the altar of the Temple, how enemies seemed to surround the young David, how a bride circumambulates around a groom under the chuppah. In each of these instances, the circle energizes and transforms the center. So “just going around in circles” is actually very powerful.

When we dance at a simcha, the center of the circle becomes an exalted space. It is where the celebrants are especially welcomed and embraced, and where an exuberant dancer can express their joy and good wishes, in what is known as “shayning”- essentially, showing off. Even in a crowded room, the circle maintains this open space at the center that allows more expansive dancing. I was once dancing with some of my Yiddish dance students from the festival in Krakow at a crowded underground nightclub where the klezmer musicians would jam until dawn. Despite the packed crowd, we were able to form ourselves into a circle which people somehow made room for. And in the center was a clear space where one or two people could spin or swing a partner, and generally dance out in a room where otherwise one could barely lift an arm.

What the circle gives, it can also take away. I’ve seen a video of mostly Chassidic dancers at the Lag B’Omer celebration in Meron. The dancers were in a large circle, and in the spacious center a couple of guys were doing lively kadatshki solos- rhythmically flinging arms and kicking legs. Then one non-Chassidic outsider was moved to jump into the center, too, and performed a somewhat awkward version of the same dance, with chaotic energy. One Chassidic dancer tried to take the interloper’s hands and partner him in a more appropriate dance, but the other dancer wouldn’t calm down. And then, the most astonishing thing happened. Spontaneously, the circle shrank and closed up, and the sacred space, now seemingly profaned, disappeared, and the rowdy dancer was absorbed into the crowd.

I used the words “sacred” and “profaned” on purpose. The center of the circle becomes a kind of sacred space, a holy ground.

G-d instructs Moses to cast off his sandals and go barefoot into this holy place. There are many opinions of why it was important for Moses to take off his sandals. Where they soiled in a way that would profane the place? (he was, after all, herding sheep). Were shoes a sign of power and conquest, and Moses need to humble himself? Perhaps, but I like this explanation I stumbled across:

In the collection Bible Borders, and Belonging, an essayist suggests that “In cultures where people remove their shoes or sandals when they enter a home, the command to Moses suggests that he is welcomed.”

I like that. Welcomed into G-d’s presence. Welcomed into a transformative experience. Welcomed into an awareness of his deep Jewishness and growing responsibility. I think I relate to that because, as a dance leader, it is my aspiration to welcome people into the circle and let them have a transformative experience.

(The Klezmatics sing "Holy Ground")

But like many would-be dancers I encounter, Moses is full of doubts, insecurities, and excuses. The Israelites won’t listen to him. He’s weak of speech. He won’t know what to say. I hear a similar litany of excuses when people are anxious about dancing. I’m awkward. I don’t know the steps. I’ll look foolish. I’m too old. I have a physical limitation. People like me don’t do that. I’m scared.

But just as it took time to observe that the bush was not being consumed, in that holy place I imagine time stretched and expanded to accommodate the long conversation. Moses remains in that holy space- he does not flee- and is convinced by G-d that he can do it. And in the dance, all you need to do is to welcome yourself onto the holy ground of the dance floor, even to the center of the circle, and take the time to let the dance transform you and connect you.

Moses is also introduced to G-d in a very personal way. Moses is provided with a name for G-d, as an introduction to the Israelites. In fact, G-d has a tangle of names. It’s rather like the White Knight in Through the Looking Glass, who says:

The name of the song is called "Haddocks' Eyes".'

'Oh, that's the name of the song, is it?' Alice said, trying to feel interested.

'No, you don't understand,' the Knight said, looking a little vexed. 'That's what the name is called. The name really is "The Aged Aged Man".'

'Then I ought to have said "That's what the song is called"?' Alice corrected herself.

'No, you oughtn't: that's quite another thing! The song is called "Ways and Means": but that's only what it's called, you know!'

'Well, what is the song, then?' said Alice, who was by this time completely bewildered.

'I was coming to that,' the Knight said. 'The song really is "A-sitting On a Gate": and the tune's my own invention.'

G-d is called Elohim or Adonai in the torah, G-d says I call Myself the G-d of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, but when asked for a name to give the Israelites, gives the cryptic Ehye Asher Ehye, I will be what I will be. Not a static name, but a name tasting of eternity. G-d’s name too invokes a journey.

And now Moses can say absolutely who sent him. Names are important- they make one noticeable, and not simply blend in with the background. The parsha is full of named individuls- the sons of Jacob are enumerated at the beginning of the Parsha. According to the rabbis as a testament to G-d’s love, to remember them by name. The midwives are named. Moses is given a name, as are his Midianite father in law and wife and son. Persons who are named become memorable, their characteristics stick with us. We begin to truly see them. In contrast are the “some guy”- ish- characters in the story: the taskmaster, the slave who is being beaten, the “no ish” who doesn’t bear witness to the taskmaster’s slaying, but then seems to be manifest as the two guys who are quarreling and let Moses know his deed is known, and ironically ask who made him their chief. These nameless characters perform functions fraught with violence, and the Torah does not invite us to remember them.

Curiously, in songs based on Jewish dancing calls, names are used, unlike in most square dance calls, where positions are called. Rather than say “head couple forward” or “First gent swing your corner”, the calls are recorded along the lines of “ Motl, Motl, tzu mir mitn punim, Yente, Yente, gey in der mit. Gitl, Gitl, gey shoyn aher, Dvoreh, gey shoyn tzurik” (Motl, look at me, Yente, go in the middle. Gitl, go there now, Dvoreh, come back now.) Where the dancers know each other, this makes sense.

As a dance teacher, I kind of hate nametags, but find them very useful. A name lets me see someone more clearly and remember who they are. My student Ray is enthusiastic and picks up quickly, his wife Beverly enjoys herself but is a little slower and rarely smiles. “Ray, that looks great! Beverly, use your other hand”.

So much of what I try to achieve when leading dancers is for them to truly see each other too, and over the course of a dance achieve a timeless joy. The same kind of intense noticing can take place, just as Moses noticed over time the burning bush not being consumed. As we pass by and interact in the dance, we see that friend Motl smiled at us, Aunt Gitl is dancing with her granddaughter Dvorah. That’s so much deeper than someone smiled, someone danced with someone else. Or, if a stranger, the dance creates an opportunity to learn their name and maybe more about them.

The art and practice of dancing itself relies on names to a great degree. What kind of dance do you want to do? What dance is that? A waltz is not a polka. A zhok has steps and is generally slow, a bulgar has different steps and music and is usually fast. Even steps and figures (patterns in space) can have names. And those names make the activity familiar. Names like Threading the needle, Over and under, Leading out; once one is formally introduced to them, evoke a specific activity. It is a way of noticing what this thing is, and how it’s different from that thing. They can become friends, rather than strangers. And with the Jewish dances, the dance names also become names of mishpokhe- family.

At the end of the parsha, G-d promises that Pharoah will release the Israelites because of a “greater might”. We achieve a greater might in this world when we are able to come together as family and as a community. Together, we can do greater good. Hineh ma tov…

And just as Moses’ journey was to gradually embody his own Judaism, it is my goal to help people embody their Judaism, from the feet up, whether born to it or borrowed, as is the case when I teach non-Jews and they find the place where their soul intersects with a Jewish soul. It requires allowing oneself to feel welcomed, to pay attention, and to let the timeless holy moment touch the soul. Oh, and it’s also a lot of joyous fun!

(Creating holy gound in Krakow, Poland. Welcoming the Shabbos Shekhinah on Friday afternoon with a backwards march)

But first, a song "Kotsk"

[Refren]

[Refrain]

Kayn kotsk furt men nit,

To Kotsk we do not ride,

Kayn kotsk gayt men.

To Kotsk we walk.

Vayl kotsk iz dokh bimkoym hamikdesh (2)

Because Kotsk is a sacred place (2)

Kayn kotsk miz men oyle-reygl zayn,

To Kotsk we must go on foot,

oyle-reygl zayn.

go on foot.

1. Reygl iz dokh der taytsh a fis,

1. "Regl" means "a foot",

Kayn kotsk miz men gayn tsi fis.

To Kotsk we go on foot,

Zingendik, tantsndik!

Singing, dancing!

In az khsidim gayen kayn kotsk,

And when Hasidim go to Kotsk,

Gayt men mit a tants! (2)

They dance as they walk! (2)

[Refren]

[Refrain]

2. Reygl iz dokh der taytsh a geveyntshaft,

"Regl" means a "custom",

Men darf zikh gevaynen tsi gayn kayn kotsk,

You have to become accustomed to walking to Kotsk,

Zingendik, tantsndik!

Singing, dancing!

In az khsidim gayen kayn kotsk,

And when Hasidim go to Kotsk,

Gayt men mit a tants! (2)

They dance as they walk. (2)

[Refren]

[Refrain]

3. Reygl iz dokh der taytsh a yontev,

3."Regl" means a holy day,

Git yontev, git-yontev, git-yontev!

A happy holiday, a happy holiday!

Zingendik, tantsndik!

Singing, dancing!

In az khsidim gayen kayn kotsk,

And when Hasidim go to Kotsk,

Geyt men mit a tants! (2)

They dance as they walk. (2)

(Kotsk sung by Henry Sapoznik with the band Youngers of Zion)

Today’s parsha, Shemot, is almost too rich. In it we have the origin story of the superhero Moses, but it reads like a dream; a fantastic tangle of interconnected themes. To name just a few: birth, death, water, blood, G-d, names, and feet. As a dance guy, I’m going to focus on, obviously, feet, but also on the many names that eponymously give this parsha its name: shemot.

The song I began this drash with, Kotsk, is about a Chassidic journey to the court of Kostsk. And this parsha concerns both a physical journey, from Egypt to Midian and back to Egypt, and also Moses’ spiritual journey, from being kind of Jewish and kind of Egyptian, to being a Jew like no other. And while Moses reconnects with his Jewishness on this journey, we discover G-d reconnecting with the Jewish people, all through being observant and sensitive. G-d hears the people and their suffering, and Moses sees, and wonders over, the burning bush. How long and how closely must one watch a burning bush to notice it is not being devoured by the flame? When Moses approaches the bush, we get the first reference to feet; G-d tells Moses to cast the sandals from his feet, as this is holy ground. This is the exquisite turning point in the journey, the still moment at the end of the pendulum’s swing. This moment is most resonant to me as a dancer and dance leader.

Just like Moses, we mostly use our feet to go places. It’s a prosaic thing, walking, running, traveling, journeying. Yet dance is not practical, we’re not trying to get anywhere. I often find myself chastising young dancers who disrupt a dance by going too fast in relation to others that “this is not a race”. No, when we dance, we’re not necessarily trying to get to some destination, in general we’re simply going around in circles. “Going around in circles” is often used to announce a pointless pursuit, but Judaism has a different view of circles.

Biblical Hebrew has a number of words to describe dance. One of the major ones is Machol, the root of which, chul, could describe turning or gyrating. In context it often refers to the dance of women- it is the word used to describe Miram and the women’s dance at the Red Sea, and has a connotation of a call and response dance-one of the simplest choreographic ideas. It is often a synonym for joy, and is frequently paired with the word for drum- tof – as in both the Miriam episode and the 150th psalm- Halleluhu betof u’machol.

Rikud has become another Modern Hebrew word for dance, but in the Torah it mostly refers to athletic capering and leaping like lambs and rams, or mountains when the Red Sea parted. Psalm 114: “Heharim rakdu k’eylim”- the mountains skipped like rams. It is also one of the words used to describe King David’s leaping, spinning dance before the Ark.

Hagag refers to processions, and gives us the word Chag for a pilgrimage festival, and more generally any holiday.

And finally, Sivuv refers to circling, or encircling. It’s the word used to describe how Joshua encircled Jericho, how worshippers encircled the altar of the Temple, how enemies seemed to surround the young David, how a bride circumambulates around a groom under the chuppah. In each of these instances, the circle energizes and transforms the center. So “just going around in circles” is actually very powerful.

When we dance at a simcha, the center of the circle becomes an exalted space. It is where the celebrants are especially welcomed and embraced, and where an exuberant dancer can express their joy and good wishes, in what is known as “shayning”- essentially, showing off. Even in a crowded room, the circle maintains this open space at the center that allows more expansive dancing. I was once dancing with some of my Yiddish dance students from the festival in Krakow at a crowded underground nightclub where the klezmer musicians would jam until dawn. Despite the packed crowd, we were able to form ourselves into a circle which people somehow made room for. And in the center was a clear space where one or two people could spin or swing a partner, and generally dance out in a room where otherwise one could barely lift an arm.

What the circle gives, it can also take away. I’ve seen a video of mostly Chassidic dancers at the Lag B’Omer celebration in Meron. The dancers were in a large circle, and in the spacious center a couple of guys were doing lively kadatshki solos- rhythmically flinging arms and kicking legs. Then one non-Chassidic outsider was moved to jump into the center, too, and performed a somewhat awkward version of the same dance, with chaotic energy. One Chassidic dancer tried to take the interloper’s hands and partner him in a more appropriate dance, but the other dancer wouldn’t calm down. And then, the most astonishing thing happened. Spontaneously, the circle shrank and closed up, and the sacred space, now seemingly profaned, disappeared, and the rowdy dancer was absorbed into the crowd.

I used the words “sacred” and “profaned” on purpose. The center of the circle becomes a kind of sacred space, a holy ground.

G-d instructs Moses to cast off his sandals and go barefoot into this holy place. There are many opinions of why it was important for Moses to take off his sandals. Where they soiled in a way that would profane the place? (he was, after all, herding sheep). Were shoes a sign of power and conquest, and Moses need to humble himself? Perhaps, but I like this explanation I stumbled across:

In the collection Bible Borders, and Belonging, an essayist suggests that “In cultures where people remove their shoes or sandals when they enter a home, the command to Moses suggests that he is welcomed.”

I like that. Welcomed into G-d’s presence. Welcomed into a transformative experience. Welcomed into an awareness of his deep Jewishness and growing responsibility. I think I relate to that because, as a dance leader, it is my aspiration to welcome people into the circle and let them have a transformative experience.

(The Klezmatics sing "Holy Ground")

But like many would-be dancers I encounter, Moses is full of doubts, insecurities, and excuses. The Israelites won’t listen to him. He’s weak of speech. He won’t know what to say. I hear a similar litany of excuses when people are anxious about dancing. I’m awkward. I don’t know the steps. I’ll look foolish. I’m too old. I have a physical limitation. People like me don’t do that. I’m scared.

But just as it took time to observe that the bush was not being consumed, in that holy place I imagine time stretched and expanded to accommodate the long conversation. Moses remains in that holy space- he does not flee- and is convinced by G-d that he can do it. And in the dance, all you need to do is to welcome yourself onto the holy ground of the dance floor, even to the center of the circle, and take the time to let the dance transform you and connect you.

Moses is also introduced to G-d in a very personal way. Moses is provided with a name for G-d, as an introduction to the Israelites. In fact, G-d has a tangle of names. It’s rather like the White Knight in Through the Looking Glass, who says:

The name of the song is called "Haddocks' Eyes".'

'Oh, that's the name of the song, is it?' Alice said, trying to feel interested.

'No, you don't understand,' the Knight said, looking a little vexed. 'That's what the name is called. The name really is "The Aged Aged Man".'

'Then I ought to have said "That's what the song is called"?' Alice corrected herself.

'No, you oughtn't: that's quite another thing! The song is called "Ways and Means": but that's only what it's called, you know!'

'Well, what is the song, then?' said Alice, who was by this time completely bewildered.

'I was coming to that,' the Knight said. 'The song really is "A-sitting On a Gate": and the tune's my own invention.'

G-d is called Elohim or Adonai in the torah, G-d says I call Myself the G-d of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, but when asked for a name to give the Israelites, gives the cryptic Ehye Asher Ehye, I will be what I will be. Not a static name, but a name tasting of eternity. G-d’s name too invokes a journey.

And now Moses can say absolutely who sent him. Names are important- they make one noticeable, and not simply blend in with the background. The parsha is full of named individuls- the sons of Jacob are enumerated at the beginning of the Parsha. According to the rabbis as a testament to G-d’s love, to remember them by name. The midwives are named. Moses is given a name, as are his Midianite father in law and wife and son. Persons who are named become memorable, their characteristics stick with us. We begin to truly see them. In contrast are the “some guy”- ish- characters in the story: the taskmaster, the slave who is being beaten, the “no ish” who doesn’t bear witness to the taskmaster’s slaying, but then seems to be manifest as the two guys who are quarreling and let Moses know his deed is known, and ironically ask who made him their chief. These nameless characters perform functions fraught with violence, and the Torah does not invite us to remember them.

Curiously, in songs based on Jewish dancing calls, names are used, unlike in most square dance calls, where positions are called. Rather than say “head couple forward” or “First gent swing your corner”, the calls are recorded along the lines of “ Motl, Motl, tzu mir mitn punim, Yente, Yente, gey in der mit. Gitl, Gitl, gey shoyn aher, Dvoreh, gey shoyn tzurik” (Motl, look at me, Yente, go in the middle. Gitl, go there now, Dvoreh, come back now.) Where the dancers know each other, this makes sense.

As a dance teacher, I kind of hate nametags, but find them very useful. A name lets me see someone more clearly and remember who they are. My student Ray is enthusiastic and picks up quickly, his wife Beverly enjoys herself but is a little slower and rarely smiles. “Ray, that looks great! Beverly, use your other hand”.

So much of what I try to achieve when leading dancers is for them to truly see each other too, and over the course of a dance achieve a timeless joy. The same kind of intense noticing can take place, just as Moses noticed over time the burning bush not being consumed. As we pass by and interact in the dance, we see that friend Motl smiled at us, Aunt Gitl is dancing with her granddaughter Dvorah. That’s so much deeper than someone smiled, someone danced with someone else. Or, if a stranger, the dance creates an opportunity to learn their name and maybe more about them.

The art and practice of dancing itself relies on names to a great degree. What kind of dance do you want to do? What dance is that? A waltz is not a polka. A zhok has steps and is generally slow, a bulgar has different steps and music and is usually fast. Even steps and figures (patterns in space) can have names. And those names make the activity familiar. Names like Threading the needle, Over and under, Leading out; once one is formally introduced to them, evoke a specific activity. It is a way of noticing what this thing is, and how it’s different from that thing. They can become friends, rather than strangers. And with the Jewish dances, the dance names also become names of mishpokhe- family.

At the end of the parsha, G-d promises that Pharoah will release the Israelites because of a “greater might”. We achieve a greater might in this world when we are able to come together as family and as a community. Together, we can do greater good. Hineh ma tov…

And just as Moses’ journey was to gradually embody his own Judaism, it is my goal to help people embody their Judaism, from the feet up, whether born to it or borrowed, as is the case when I teach non-Jews and they find the place where their soul intersects with a Jewish soul. It requires allowing oneself to feel welcomed, to pay attention, and to let the timeless holy moment touch the soul. Oh, and it’s also a lot of joyous fun!

(Creating holy gound in Krakow, Poland. Welcoming the Shabbos Shekhinah on Friday afternoon with a backwards march)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed