Lines of opposition: Felix Febich, Judith Berg and a theory of Yiddish line.

The Yiddish movement repertoire has analogs in other European dance forms, with, of course, a Yiddish flavor. And there is certainly a vocabulary of Yiddish gestures. But I want to look more broadly at an internalized aesthetic that manifests in whole body shapes and lines and which has offered, and I believe, continues to offer, particular choreographic interest.

A few years ago I found myself standing at a graveside for the funeral of the Polish born dancer, choreographer and actor Felix Febich with whom I worked as a dancer and as an assistant and “handler” at KlezKamp, along with a number of others who had been touched and influenced by his life. The officiating rabbi had made the decision that, rather than those assembled tossing a few clods of earth into the open grave, we as a community would cover his coffin with earth. It was at once brutal and tender, both literally burying, and tenderly tucking into bed

There is a palpable finality to burying someone, but as I wielded the shovel, I found myself noticing that the area near his head had not been sufficiently filled in, and as I shoveled earth there, it was as if I was tucking Felix in for his long sleep.

A most appropriate thing to feel, as contrasts and dichotomies played such an important part in Felix’s life and art. His life story, which he would often narrate, and had polished to a fascinating and well-crafted tale, was filled with contrasts of triumphs and terrors, hope and despair, humor and tragedy and these elements were enfolded in his and his wife Judith Berg’s theory of Yiddish dance.

I had the privilege of working with and learning from Felix off and on for a number of years, absorbing as best as I could his experience, and the experience gained from his teachers and mentors, and they have become a great and important influence on my own understanding of Jewish dance. I also came to realize that he and Judith were not stylistically suis generis. A number of dance artists, going back at least to Baruch Aggadati, seemed to adhere to the same aesthetic.

Felix was Born 5 August, 1917 in Warsaw. Warsaw’s Jewish population at that time was

a mix of secular Jews, religious Jews, and Chassidim. He worked in his family’s restaurant, but would sneak off to see Yiddish theater, and yearned to join, particularly Michael Weichart’s Yung-teater (Young Theater) in Warsaw. He did, and in 1936 met Judith Berg, who was choreographing the troupe’s production of “Wozzeck.” Ms. Berg was a student of the German Expressionist dance pioneer Mary Wigman, and is perhaps best known as the choreographer of The Dybbuk, and danced the part of Death in the famous Dance of Death.

The Yiddish movement repertoire has analogs in other European dance forms, with, of course, a Yiddish flavor. And there is certainly a vocabulary of Yiddish gestures. But I want to look more broadly at an internalized aesthetic that manifests in whole body shapes and lines and which has offered, and I believe, continues to offer, particular choreographic interest.

A few years ago I found myself standing at a graveside for the funeral of the Polish born dancer, choreographer and actor Felix Febich with whom I worked as a dancer and as an assistant and “handler” at KlezKamp, along with a number of others who had been touched and influenced by his life. The officiating rabbi had made the decision that, rather than those assembled tossing a few clods of earth into the open grave, we as a community would cover his coffin with earth. It was at once brutal and tender, both literally burying, and tenderly tucking into bed

There is a palpable finality to burying someone, but as I wielded the shovel, I found myself noticing that the area near his head had not been sufficiently filled in, and as I shoveled earth there, it was as if I was tucking Felix in for his long sleep.

A most appropriate thing to feel, as contrasts and dichotomies played such an important part in Felix’s life and art. His life story, which he would often narrate, and had polished to a fascinating and well-crafted tale, was filled with contrasts of triumphs and terrors, hope and despair, humor and tragedy and these elements were enfolded in his and his wife Judith Berg’s theory of Yiddish dance.

I had the privilege of working with and learning from Felix off and on for a number of years, absorbing as best as I could his experience, and the experience gained from his teachers and mentors, and they have become a great and important influence on my own understanding of Jewish dance. I also came to realize that he and Judith were not stylistically suis generis. A number of dance artists, going back at least to Baruch Aggadati, seemed to adhere to the same aesthetic.

Felix was Born 5 August, 1917 in Warsaw. Warsaw’s Jewish population at that time was

a mix of secular Jews, religious Jews, and Chassidim. He worked in his family’s restaurant, but would sneak off to see Yiddish theater, and yearned to join, particularly Michael Weichart’s Yung-teater (Young Theater) in Warsaw. He did, and in 1936 met Judith Berg, who was choreographing the troupe’s production of “Wozzeck.” Ms. Berg was a student of the German Expressionist dance pioneer Mary Wigman, and is perhaps best known as the choreographer of The Dybbuk, and danced the part of Death in the famous Dance of Death.

Judith felt that Felix needed dance training and became his teacher. Felix studied dance with Judith, but she encouraged him to study with a male dancer, as he was picking up too many of her mannerisms and his dance looked, to her, effeminate. This strikes me as a notable comment, as it was a typical anti-Semitic trope to accuse Jewish men of being feminine. He also had to rebuild his body from an academic to an athletic one. So, he studied ballet and modern German expressionist dance. Being a short man, he commented to me on how he used line to make himself appear bigger, with expansive negative spaces, like a hand held well over the head.

Felix escaped Poland alone during the war and danced a few steps ahead of the Nazis throughout Europe performing while being chased, bombed, arrested, etc. He met up with Judith again, in Bialystock, and they performed all over Soviet Russia, in Odessa, Baku and Ashkabad. In Ashkabad Felix married Judith because the landlady wouldn’t let them cohabit otherwise.

The dances of Judith and Felix incorporated Jewish gestural language in enactions of ritual and folk culture from songs and stories. Their dances tended to the narrative vs. abstract. He once criticized a performance in his honor of mine the deconstructed some of his movements, saying “so, you can turn, it doesn’t MEAN anything”.

Felix escaped Poland alone during the war and danced a few steps ahead of the Nazis throughout Europe performing while being chased, bombed, arrested, etc. He met up with Judith again, in Bialystock, and they performed all over Soviet Russia, in Odessa, Baku and Ashkabad. In Ashkabad Felix married Judith because the landlady wouldn’t let them cohabit otherwise.

The dances of Judith and Felix incorporated Jewish gestural language in enactions of ritual and folk culture from songs and stories. Their dances tended to the narrative vs. abstract. He once criticized a performance in his honor of mine the deconstructed some of his movements, saying “so, you can turn, it doesn’t MEAN anything”.

Returned to Poland to find their families and neighborhoods lost. They couldn’t imagine dancing there again. “How can you dance in a Cemetery?” is how he put it.

However, they were invited to visit home for Jewish orphans. The children touched their hearts, they felt a responsibility to bring them a positive Yiddishkayt. First they performed for them, then they taught them about the Jewish holidays, songs, dances and eventually developed a school and a company.

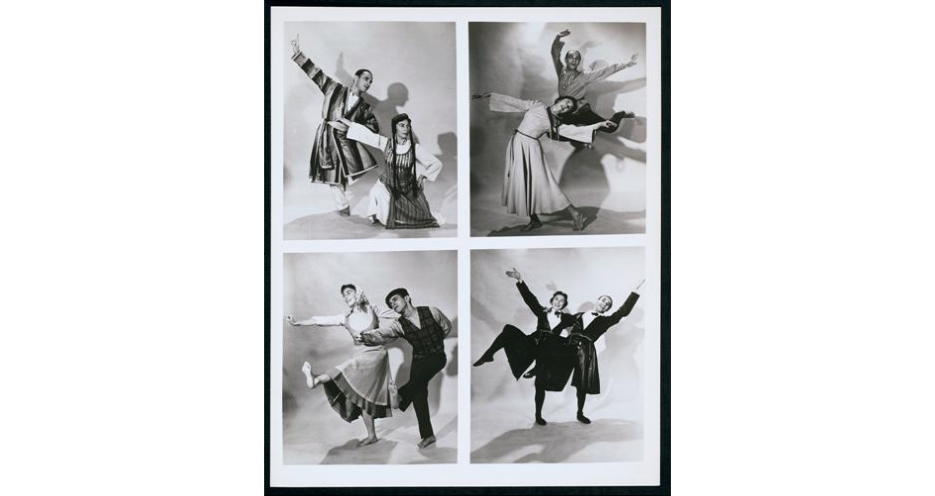

Judith and Felix performing Elimelech at the Kinderheim Jewish orphange

However, they were invited to visit home for Jewish orphans. The children touched their hearts, they felt a responsibility to bring them a positive Yiddishkayt. First they performed for them, then they taught them about the Jewish holidays, songs, dances and eventually developed a school and a company.

Judith and Felix performing Elimelech at the Kinderheim Jewish orphange

All along they were thoughtfully analyzing their dances and developing a theory of Jewish dance:

These are excepts from an interview with Judith Brin Ingber included in her book Seeing Israeli and Jewish Dance, but these were concepts I often heard him explain:

When I started to analyze this [I realized that] when we are dancing, our movements are not round. Our movements are…like the Shin…the Hebrew block letters…those broken angular lines…All these things, all these are Hebraic in style which nobody realized, that these are the images.

Then another thing we discovered, I discovered in movement…Opposition: Jewish mood has two opposite moods: joy and sadness

This opposition also expresses when the Hasidim are dancing on bent knees yet reaching out and the bent knees standing. The body, for example, they take the ritual cord or belt, the gartel, to separate the body physical or sexual from the spiritual.

(or as I like to say, the part that works and prays from the part that has “functions”)

The division, the belt dividing the body in two parts, pulling in two different directions. So we discovered the opposition in the body. So when the arms go one way, the head goes the other way... Opposite, always opposition. This was the character, the style of the dance.

The soul, the Jewish soul, which is torn between joy and sadness…this reflects in our

body also when we are dancing. It’s connected. We found the connection, the reason why

we are moving in this way.

I find the idea of the tension of joy and sadness a little lachrymose. I prefer to liken Jewish movement to the way I describe the music as having a tension between Ecstasy and Longing, which I guess makes me a closet Chassid.

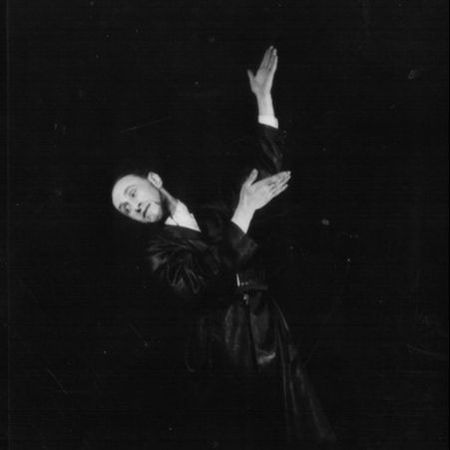

One of Felix’s stated inspirations, and I find this illuminating, is the in the forms of the Hebrew letters. Below, the Hebrew letter Aleph, and Baruch Aggadati in a pose reminiscent of that form:

Among the hallmarks of Hebrew typography are acute negative shapes, asymmetry, and little flags at the ends of lines. I find the acute negative shapes the most significant.

Yvette Metral (niece of Judith Berg) called these types of shapes “grotesque”- not something I agree with, and a very western lens, because where those shapes are seen in western art, it is usually representing the grotesque- the fantastical and misshapen, gnomish and convoluted

These shapes need not be craven, something unfortunately often depicted in Yiddish dance, but may be seen, rather, as constrained. The body lines are characteristically angular vs. the catenary curves of classical art and ballet and have a middle eastern, rather than a classical, aesthetic.

I like to liken it to difference between topiary (neat, symmetrical, architectural and artificial) and bonsai (representing a tree shaped by wind and natural forces) It is an aesthetic of precariousness. I suspect this represents a conscious non-conformity with Western aesthetic models, in line with the baked-in Jewish tendency to otherness: what they do, we don’t do.

It could be illuminating to experience embodying this aesthetic for yourself, so if you wish you can follow along on this little etude I developed that I and others find efficient and enjoyable. You will need a small handkerchief or bandana.

Handkershief Etude

This experience may make you more attuned to and resonant with those shapes seen in other modern dancers of the era. The earliest example of this aesthetic in a dancer that I have come across is in the work of Baruch Aggadati who was born Jan 8 1895 in Bessarabia, grew up in Odessa where he received ballet training, and migrated to Palestine in early 1900s. Much of his solo work involved the representation of Jewish types, and there is a consistency in both his artwork and in photographs of him.

Yvette Metral (niece of Judith Berg) called these types of shapes “grotesque”- not something I agree with, and a very western lens, because where those shapes are seen in western art, it is usually representing the grotesque- the fantastical and misshapen, gnomish and convoluted

These shapes need not be craven, something unfortunately often depicted in Yiddish dance, but may be seen, rather, as constrained. The body lines are characteristically angular vs. the catenary curves of classical art and ballet and have a middle eastern, rather than a classical, aesthetic.

I like to liken it to difference between topiary (neat, symmetrical, architectural and artificial) and bonsai (representing a tree shaped by wind and natural forces) It is an aesthetic of precariousness. I suspect this represents a conscious non-conformity with Western aesthetic models, in line with the baked-in Jewish tendency to otherness: what they do, we don’t do.

It could be illuminating to experience embodying this aesthetic for yourself, so if you wish you can follow along on this little etude I developed that I and others find efficient and enjoyable. You will need a small handkerchief or bandana.

Handkershief Etude

This experience may make you more attuned to and resonant with those shapes seen in other modern dancers of the era. The earliest example of this aesthetic in a dancer that I have come across is in the work of Baruch Aggadati who was born Jan 8 1895 in Bessarabia, grew up in Odessa where he received ballet training, and migrated to Palestine in early 1900s. Much of his solo work involved the representation of Jewish types, and there is a consistency in both his artwork and in photographs of him.

These lines were also visible in the works of Nathan Vizonsky, immigrant choreographer of the Meyer Weisgal pageant Romance of a People for 1933 ChicagoWorld’s Fair, and author of

10 Jewish Dances, with illustrations by Todros Geller, and Benjamin Zemach who was nominated for Oscar for dance in SHE (1935- on youtube),

and invited by Meyer Weisgal to choreograph The Eternal Road in NYC- with music by Kurt Weill, and directed by Max Steinhart.

10 Jewish Dances, with illustrations by Todros Geller, and Benjamin Zemach who was nominated for Oscar for dance in SHE (1935- on youtube),

and invited by Meyer Weisgal to choreograph The Eternal Road in NYC- with music by Kurt Weill, and directed by Max Steinhart.

These various nodern dance artists were not pulling these shapes and ideas out of thin air or their imaginations. They can be found in the expressive dancing of just plain Jewish folk. Here is a solo performed by a contemporary Hasid at a simcha in Israel.

In conclusion, I’d like to dedicate this post to the memory of Felix Febich.

In conclusion, I’d like to dedicate this post to the memory of Felix Febich.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed