I found it very interesting, then, to recently come across an idea that has been getting a bit of press lately, put forth by the sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his book The Great Good Place. He describe what he called “Third Places”, social surroundings that are separate from the two usual social environments where we meet and interact with others. Oldenburg calls one's "first place" the home and the people the person lives with. The "second place" is the workplace or school—where people may actually spend most of their time. Third places, then, are "anchors" of community life and facilitate and foster broader, more creative interaction.[1] In other words, "your third place is where you relax in public, where you encounter familiar faces and make new acquaintances. Examples include cafes, clubs, bars (think Cheers), places of worship, public libraries, gyms, bookstores, stoops and parks.

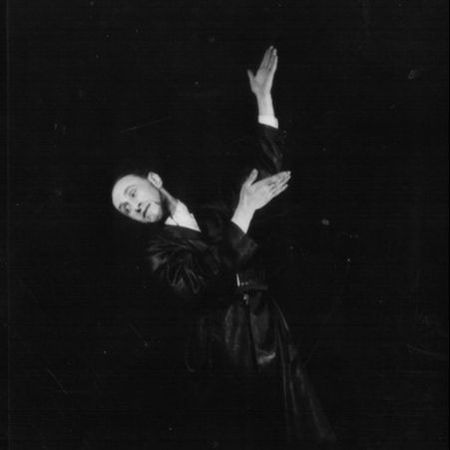

From my own experience I suspect that a third place can also be an event in time. Leading dance at festivals and such I’ve observed the powerful socializing effect of dancing together, and how it fosters conversations and friendships. Especially when the dance becomes a regular event. So, in the respect, a dance Can be a third Place.

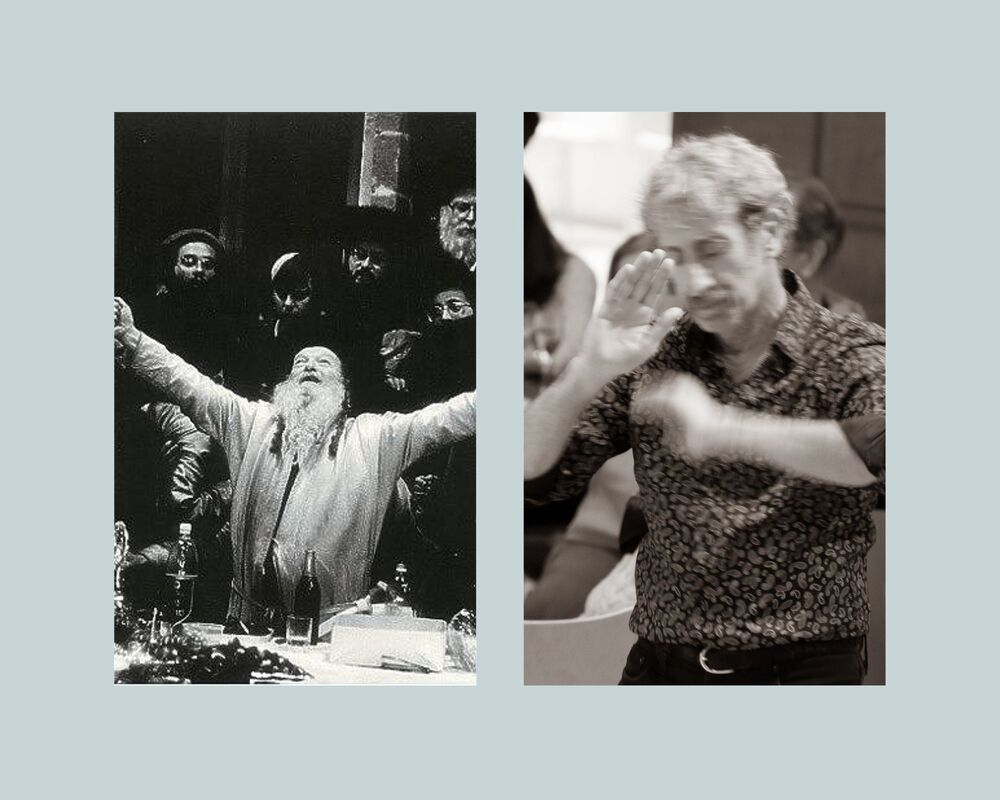

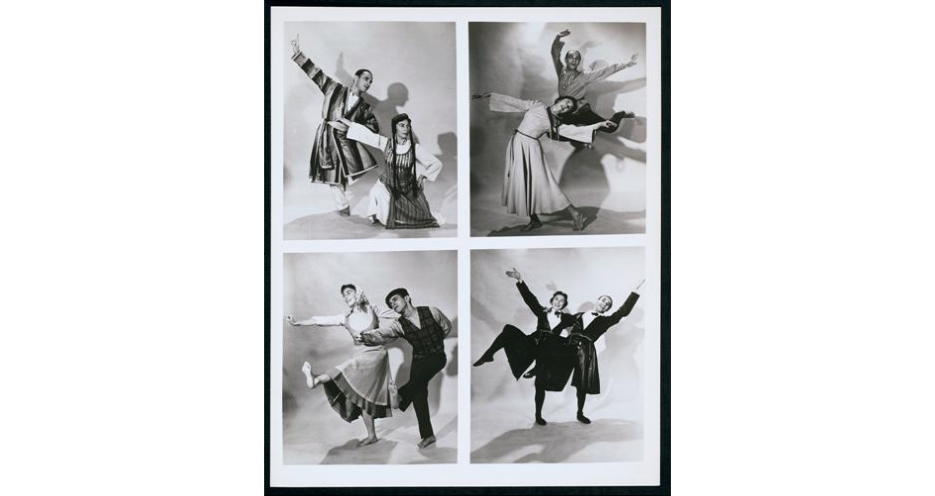

To support that thesis , let me present this little documentary by filmmaker David Dolinsky presenting the very successful DC Klezmer Workshop Group, which meets regularly and where I have several times had the pleasure of leading dancing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed