I’m a fan of the animated characters Wallace and Gromit. Rendered in brilliant stop motion, Wallace is a middle aged British fellow, good hearted and inventive, and Gromit is his highly intelligent and mutely expressive dog. In one of their short films, A Close Shave, which involves a knitting lady love interest, a nefarious bulldog, and a clandestine flock of sheep, there is a chase scene, with the sheep and the knitting lady prisoners in a speeding truck driven by the bulldog. Wallace, in hot pursuit on a motorcycle, somehow manages to bridge the gap between the truck and his motorcycle using a long straight ladder and his own body. The sheep then make their way across Wallace and the ladder and pile willy-nilly on top of the motorcycle, with Wallace perched atop the now vertical ladder. This of course is not a tenable situation, even in an animated feature, so Wallace calls down to the sheep:

“Get yourselves organized down there!”

And after cutting away, the next shot reveals the sheep now arranged like Chinese acrobats in an upside-down pyramid on the ladder. Still precarious, but much better prepared for whatever road hazards await them.

In this week’s parsha, Bemidbar, which means In the Wilderness, G-d speaks to Moses in the Wilderness of Sinai. A wilderness is a perilous place, and the Israelites, recently escaped, liberated, and given Torah, are literally in the middle of nowhere- they are neither in the old bad place they called home, nor in their new, yet to be disclosed place.

And yet, even without a home, they need to begin to function as a nation. And so G-d, through Moses, calls down to them: “Get yourselves organized down there!”

Actually, what G-d commands through Moses is to take a count, a census of the people. Some commentators feel that G-d so loves his people, that he finds many opportunities to count them. But the words used in the parsha are “Seu et Rosh”: Raise the Heads of the people so they can be counted, and also see one another. I prefer to believe that, since G-d clearly knows how many Israelites were camped together, the counting was an opportunity for the new nation to take stock of themselves. Not “Wow, there’s a lot of us” but very specifically, each individual, each one person, plus One person, plus One person as part of a family, and those Ones plus other Ones, as part of a tribe, and all those Ones together as part of a nation.

Here’s a question, a kind of treasure hunt, for the young people. Kids, which tribe had the most? Which had the least? Look at the parsha and try to figure it out. I’ll ask you again in a minute.

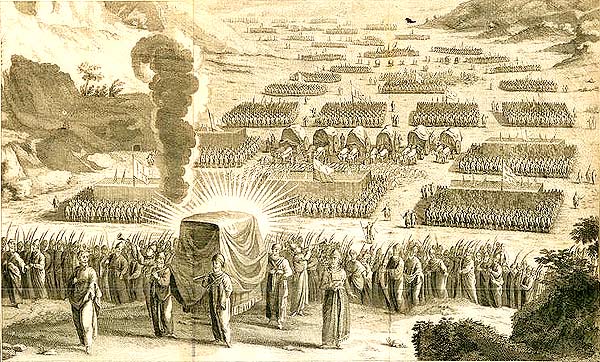

Actually, two censuses are taken, one military, the other religious. In the first, only men over 20 who are capable of fighting, and not of the tribe of Levi, are counted. Later, their arrangement around the Mishkan, the portable Tent of Meeting, is determined. As a choreographer, I can tell you it’s good to know how many bodies you are dealing with when you try to arrange people in space. It reminds me that Busby Berkely, the golden age Hollywood director and choreographer of those spectacular, kaleidoscopic dance numbers in old musicals like 42nd Street, started his career organizing marching drills in the army.

So kids, which tribe had the most men over 20? (Judah, with 74, 600) Which had the least? (Menasseh, with 32,000)

If you put those two tribes together, which add up to 106,600 men, on one end of a scale or one side of a boat, which two tribes could you put together on the other side, to more or less balance them? I won’t ask for an answer, but you can see why the information might be useful: for instance, if you’re trying to have even columns marching, or distribute your strength around the Mishkan.

I’ve discovered that there is a pretty intimate relationship between the military, and counting, and dance, which is one of the things that makes this parsha fascinating for me.

There is an important French renaissance dance treatise, Orchesography, written by Thoinot Arbeau, first published in 1589, which begins its discussion of the social dances of the day by talking about military marching! This makes sense, really, because an army doesn’t simply walk to its destination, it must move in close formation and march all on the same foot and all at the same time, or they would bump into one another. Like a dance, they need to keep in time and in step. In order to keep in step, they march to the sound of a drum- with everyone stepping on the 1st and 5th drumbeat of an 8 count rhythm. The soldier doesn’t have to count, the drum does that for him. Arbeau even goes on to estimate the length of two strides, and how many drumbeats it would take to travel a league (about 1,666 if you must know).

My former dance partner, the rebbetzin Sharona Paller Rubinstein, made an interesting observation and guess on a visit to Israel, and specifically the excavations at the southern part of the temple mount. There, some stairs leading to the gates to the temple had been excavated. She saw that the stairs had a rhythm- one narrow step, followed by one broad step, over and over. To walk up the stairs required two climbing steps, then one more level step before climbing again. Up, Up, Across. Short, Short, Long. Since we know music was played by musicians at the temple, she wondered if a rhythm was played that coordinated with the climbing rhythm. For example, the rhythm of our modern melody for Shir HaMalot (a song of ascents!). How much more orderly and powerful and peaceful would it have been, if the multitude of Israelites surged up the stairs in stately unison, in time with the music, than if they simply queued up and struggled forward. In that case, it would be the musicians, combined with the architecture who, like the military drummers, kept everyone in step and cooperating.

Back to the subject of counting numbers, let me share an interesting, and for me, ultimately profound, approach to dance teaching I stumbled upon. I taught for ten consecutive years at the Festival of Jewish Culture in Krakow, Poland. I developed a loyal group of repeat students, and with a limited repertoire of Yiddish dances to teach, I would try each year to come up with a fresh approach to the material. One year I thought I’d take inspiration from counting songs, like Echad me Yodea (Who Knows One), and assign a dance or dances to each number from one through eight. Two was easy- that’s the bouncy walk of the freylekhs- the big kaleidoscopic circle dance we now tend to call the “hora”. Three- the waltz and similar dances. And so on up through Eight. Eight for the essential Jewish square dance, the sher, for four couples, or eight dancers. But ONE had me stymied. What kind of dance could I associate with one? And then I thought, and I must admit at the time I thought it was a cop-out, let’s say One is the transition from standing on two feet to taking all the weight onto one. The sway. The prelude to a step. (You can do that in your seat- shift to one sitting bone, or cheek, if you will, then the other.) I explained to the dancers (and to myself) that this is the most elemental atom of dance. That when you shift your weight, you’ve accomplished a lot. I had them point their thumbs at their chests, and say Here I Am, with each weight shift. And then, gesturing outwards, There You Are. I discovered that, for the dancers, knowing and appreciating that the change of weight, or a change of weight with a step, was a sufficient accomplishment, gave their dancing incredible clarity. If I said “Take 3 steps forward” I didn’t get some random movement forward. I got precisely 3 steps, and the readiness to do something else. A pause, a kick, as stamp, a clap.

We used that “Here I Am” step and gesture during an outdoor dance we held on Friday afternoon. At the conclusion of the dance party, we enacted a backwards march, an eastern European custom that has become part of the culture of KlezKanada. We walk backward as if welcoming Hamalka Shabes- the Sabbath Queen and bride, into our presence. Walking backwards as a sign of respect, so that we don’t turn our backs on the one we are honoring. As we started the backwards march with just a sway, I had the crowd repeat the “Hear I Am” gesture, and raise their heads, and look around: at each other in the crowd, at the square, and at the Jewish dancing happening in public in a square in Krakow. It was a very profound moment of being present. So many individuals so many “ones”, and even among the mostly non-Jewish participants, a sense of a collective Jewish neshome, a Jewish soul.

When we Seu et Rosh- raise our heads- we see who we are and where we are in relationship to others. An individual, and part of a collective, both and at the same time. In dance we get to be like the scientific definition of light: both a particle and wave. Individual agents, and a part of a greater movement. If you have the custom of connecting with your neighbors during a song- holding hands, linking elbows, holding shoulders, and swaying to the music, you’ve felt that sense of being an individual and a group in your kishkes- in your gut.

We’re coming to the conclusion of another kind of Jewish counting- that of the Counting of the Omer. A friend on Facebook has been posting the daily count, along with a bit of Talmud wisdom, so I’ve been more keenly aware of the counting this year. Apart from its ancient biblical purpose, the counting of the omer for us is now a way of counting the march from Passover and Exodus from Egypt to Shavuos and Revelation at Sinai.

Of course, I’m going to bring this around to dance. It is in the scene at the Sea of Reeds, after the Israelites had successfully crossed through the Sea of Reeds, and Moses has recited his song of praise, it is at this moment that the Torah for the first time finds it important to mention dance. Not that no dancing ever happened in history before this, but this was a monumental and historical dance: Miriam the prophetess takes and timbrel in her hand, and the women go after her, with timbrels and dances: b’tofim u bim’chalot. The word used here, machol, is one of about a dozen words used for dance. Machol is often used to describe the dances of women, it’s root, chul, can mean whirl or gyrate. It is also almost a synonym for joy. Psalm 150 includes my favorite line: Halleluhu b’tof u machol- Praise G-d with drum and dance. There we go again, with drums and movement, as we heard from Arbeau!

But it wasn’t just Miriam and the women who danced (and I’m of the opinion that the men danced too, only the bible ascribes poetry to the intellect of Moses, and dance to the emotion of Miriam). No, according to psalms, even the hills and mountains skipped like rams and lambs: “Rakdu Heheharim”. There’s another common biblical word for dance –rikud. (Both machol and rikud have become the modern Hebrew words for dance). Rikud has a more masculine or animal connotation- it’s how lambs and rams and skip and jump. It is one of the words used to describe how King David danced before the ark as it was brought into Jerusalem. He skipped, jumped, whirled. I suspect he danced backwards some, beckoning and ushering the ark forward. There is a popular expression “dance like no one is watching”. I strongly disagree with that. David’s dance was public, a tribute and an offering, and so he danced with all his might, all his intention. Rikud has the implication of high energy showing off. People all around were watching, David I’m sure was aware G-d was watching, and David’s wife was watching, thought she didn’t much care for the dance. But David didn’t care, she wasn’t the intended audience. His audience was greater, and higher.

At Sinai, there was the worst example of dancing as if no ONE is watching: the dance around the golden calf. It was not pretty. It was wild, unbridled, self-indulgent. The people did not Seu et Rosh- raise their heads to look around and be their higher selves.

Rather, for us Jews, dance is frequently understood not just as a recreation, but as a gift to give. We dance at a wedding not just because the band is good (one hopes) but because dancing is a way of fulfilling the mitzvah of gladdening the bride and groom. I help lead dancing at a lot of parties, and I’ve seen a lot of “I came, I ate, I texted, I left”. That is not contributing to the joy of the party. And the funny thing is, when you give joy, you get joy. If all you feel up to is joining hands in the group machol- following the leaders, that’s great. If you can do something extra- the showy rikud of the kozatky, say, or juggling, or some other stunt, even better. That’s a way to raise up the mitzvah. It’s also an opportunity to raise your head and say “here I am” and “there You are”. And realize, here We are together.

That feeling doesn’t have to be limited only to weddings. At that same festival in Krakow, Poland, which I talked about earlier, where we did the backwards march, I taught, as I usually teach, the wonderful old Jewish square dance, the sher. It used to be a staple at every wedding, and for good reason. Here’s a case study in why. In my class in Krakow, I had a number of students who would show up yearly, and who had become friends with each other and with me. When I taught the sher that year, I created a square of some of those dancers, who had previously learned the dance, to be my demonstration square. After walking through the dance, I got to dance the sher with these people I had gotten to know over the course of several years. Many of them spoke little or no English (I had an interpreter to help with teaching the class). But as we danced the fifteen or so minutes of the dance together, it was like a gathering of good friends or the kinds of family members that you love, but only get to see occasionally. We smiled, we circled, we crossed paths and twirled together, and we were even able to make little jokes and pay little compliments, without speaking a word. For me, and I’d like to believe for the others, happy little endorphin bombs were going off in my brain. It was just delightful and lovely.

That is what dancing to me should be. When you count yourself in, when you dance with and for each other, you raise yourself up and you raise up the group. It becomes not merely a formal exercise of counts and positions, although it helps to learn and appreciate what the counts and positions are. But that is easier than it seems, if you raise up your head to see where you are and what others are doing, and relax a bit and let yourself get swept up. You can enjoy those moments of being an individual and being part of a group, maybe in alternation, maybe simultaneously. Or you may just notice that you, and the people around you, are immensely happy and in the moment.

In the workshop and party coming up, you have an opportunity to have a taste of what the Israelites experienced in this parsha. If dance is not familiar to you, a kind of scary unknown territory, a wilderness if you will, I invite you to Seu et Rosh, raise your head and count yourself in, and dare to be an individual within the group. My hope is that we can create, for a little while at least (and maybe that is the best we can hope for in this life) a sheyner and beserer velt. A better and more beautiful world. A tam olam haba- a taste of the world to come. And what better activity for a shabes?

Gut shabes- Shabbat shalom.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed